A WORD ON

UNDERSTANDING METALS

Gold, the most precious of metals

Let’s start with the king of all precious metals – gold.

Head of Commodities

OFI INVEST ASSET MANAGEMENT

PRODUCTION

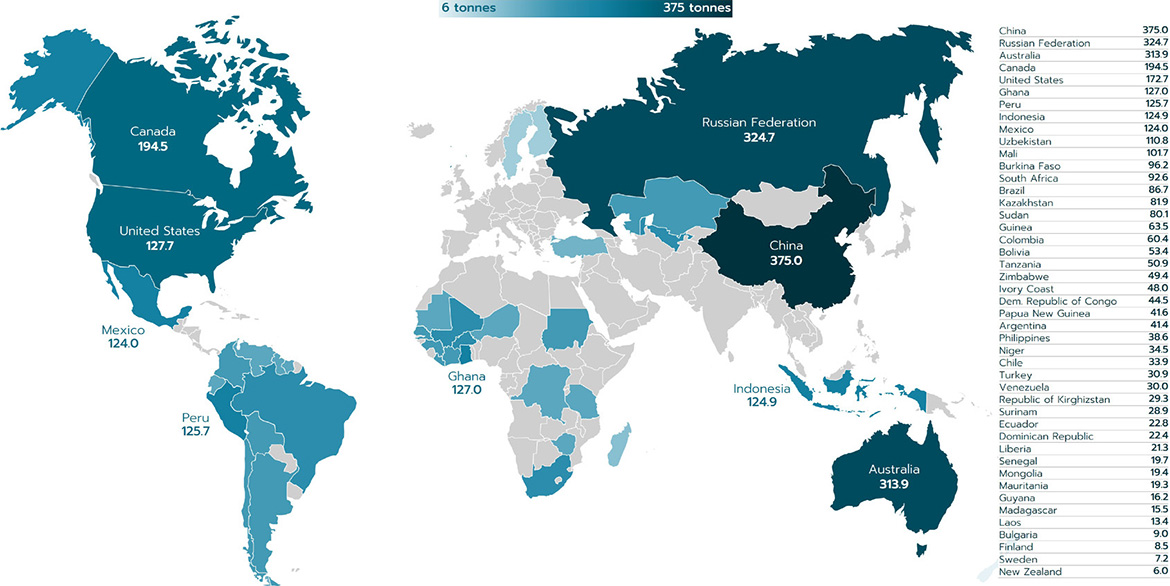

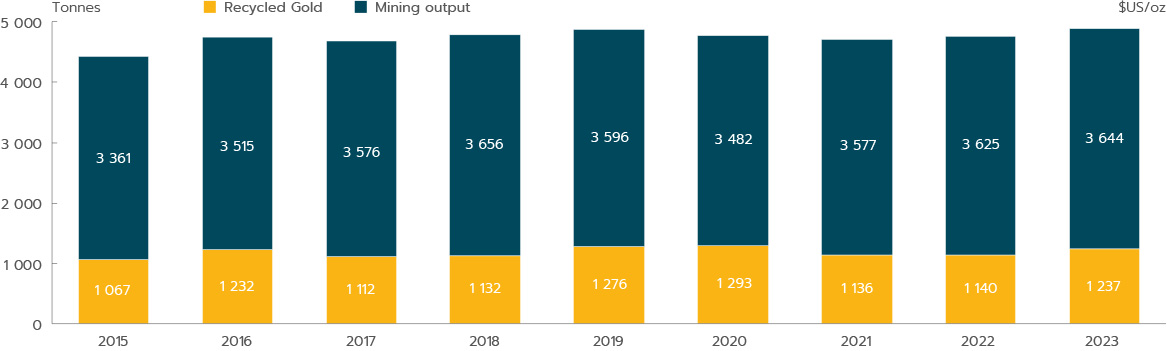

Gold output has been relatively stable for almost 10 years amounting to 3,644.4 tonnes in 2023, according to the World Gold Council. South Africa was long the world’s largest producer, with its market share rising as high as 62% in 1970. But by 1990, its market share had fallen back to 26% in 1990 and to 2.55% in 2022. The main cause of this is the depletion of mines, with production driven down by lower ore concentrations in deposits.

China is now the world’s largest producer, with market share of slightly more than 10%, followed by Russia and Australia, which each account for a little more than 8% of global output, followed by Canada (5.36%) and the United States (4.76%).

Stability of production has made possible by the development new deposits, with Africa and Central Asia beginning to play greater roles. But the problem is that output appears to have stalled somewhat.

Discoveries of new gold deposits are increasingly scarce, with the last large ones going back to the mid-2000s. Discoveries over the past 10 years account for just 6% of all gold found since 1990. As a deposit takes on worldwide average 17 years to be put into operation (source: IEA), it can be assumed that the most promising sources of production are now in operation.

This is why experts say that, as mines age, production could very soon begin to decline irremediably. As proven reserves currently amount to 59,000 tonnes, based on current output, those reserves could be exhausted by… 2040!

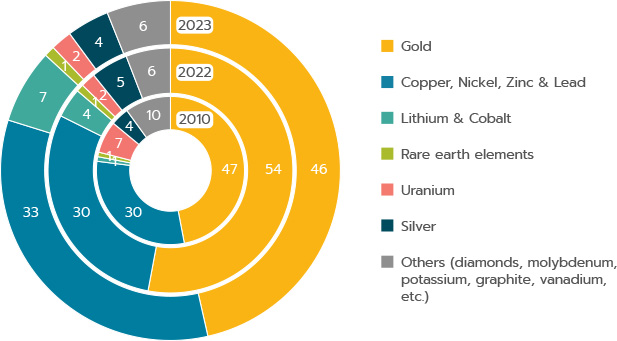

And this is not due to a lack of investment in exploration. While budgets are now lower than in the 2010s, they are still high. Gold exploration alone currently swallows up 46% of mining groups’ metal exploration budgets.

Goldmining output amounts to a little more than 3600 tonnes per year and accounts for three quarters of supply. The other quarter comes from recycling, with a little more than 1200 tonnes. Total annual supply amounts to about 4800 tonnes.

The main producers are China (the only one with more than 10% of global output), Russia, Australia, Canada and the US.

Mining output has plateaued over the past several years and, due to the lack of major discoveries in recent years, is expected to decline in the coming years. Recycling will thus become increasingly necessary for balancing supply and demand.

However, for several reasons, although goldmining output is expected to decline, a gold shortage is unlikely for some time to come.

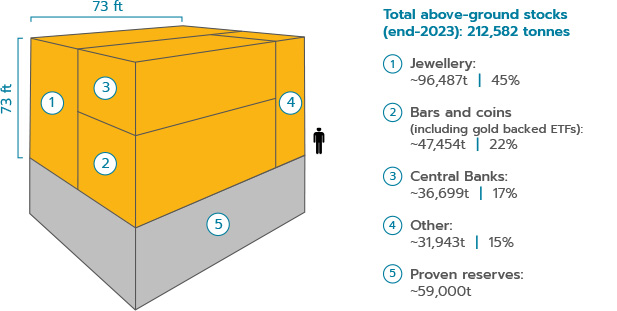

First of all, gold is an almost indestructible metal. Gold that is already mined therefore remains available. While some of it can’t be moved or is otherwise hard to recovery (see the section on recycling below), we estimate that a little more than 212,000 tonnes of gold have already been extracted – enough to fit in a 22-meter cube.

The recycling of gold may therefore serve as an important complement to mining production in ensuring balance between supply and demand. This has actually already begun, given that, in the past 10 years, recycled gold has regularly accounted for about 25% of supply.

And, second, these are only reserves, which are defined as the portion of a metal that is underground and mining of which is technically and economically feasible. Reserves are not the same as resources, which are the estimated quantity of a metal in the earth’s crust.

Over time, if gold prices rise and/or new technologies make it possible to access resources that are today unfeasible, this portion of resources will become an exploitable reserve and would push back gold’s end-date.

As of the end of 2019, gold resources were estimated by Metals Focus at 183,240 tonnes.

CONSUMPTION

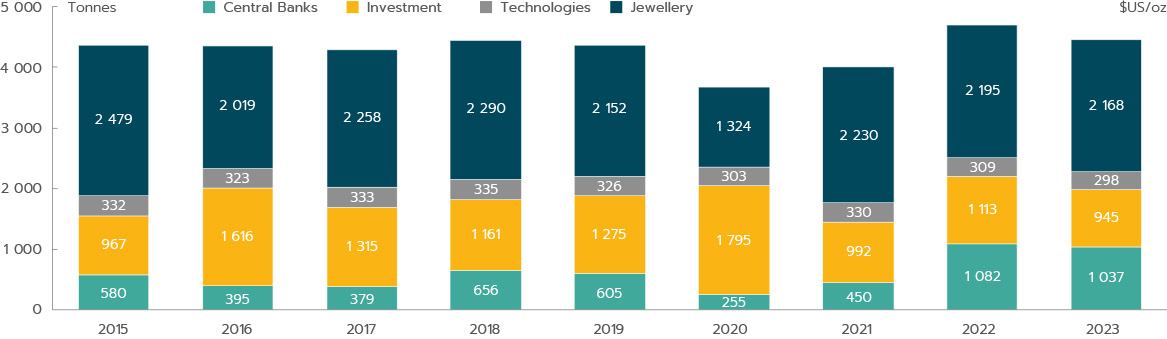

There are four main areas of gold consumption: jewellery, the tech industry, investment and central banks. Demand has been rather stable over the past 10 years, at about 4500 tonnes per year.

Jewellery is the main consumer, with market share fluctuating between 50% and 60% of global demand. Demand in this sector is only marginally elastic to gold prices (the higher the price, the more demand tends to fall) and economic uncertainty (the more worried investors get, the more they invest in gold as a store of value), in particular in China and India. These are the two largest consuming countries, alone accounting for almost half of global demand.

Historically, India has been the biggest buyer of gold, mainly for cultural reasons. Indians often provide their daughters with a dowry when they marry. They do so because all Indian couples’ goods are placed under the husband’s responsibility, with the exception of gold. Dowries are hence a way for Indian families to protect their daughters in the event of divorce. The other reason is legal in nature. Until recently, Indian law granted no rights to daughters in successions. Building up a dowry was therefore a means for parents to pass on wealth to their daughters. That law has been amended, but the traditions remain.

Recently, Chinese demand has held up rather well, driven by the resumption in weddings in 2023 after the end of the “zero-Covid” policy and by the quest for assets regarded as safe havens, amidst a sluggish real-estate sector.

Industrial demand is relatively stable over time and amounts to between 7% and 8% of total demand, or between 300 and 340 tonnes per year. Electronics and microprocessors alone account for almost 80% of this demand, with gold being used for its very high conductivity and its ductility. Because of this sector’s low share of demand for gold, even a significant economic slowdown would not have a heavy impact. Hence, in 2020, despite the pandemic, gold demand in this sector remained slightly above 300 tonnes.

The sector whose share of demand is most likely to change is investment broadly defined, i.e.; purchasing of coins and ingots, investment through exchange-traded funds (ETFs), offering passive exposure to gold) and central bank purchases. Investment accounts for a total of between 30% and 40% of demand, depending on the period.

The reason investment demand is so volatile is its financial character; i.e., it is a function of gold’s value compared to the other investment products available.

Factors determining financial demand

Gold is one financial asset among others. When investors make their allocations, they choose from among various assets available to them. In this competition, gold – like other commodities – starts with a disadvantage: unlike equities, which pay out a dividend; bonds, which pay out interest; or real-estate, which produces rental income; gold provides no income during its investment period. For this reason, investor interest in gold will rise as remuneration from other asset classes tends to decline. In particular, it becomes more attractive as the risk-free rate declines.

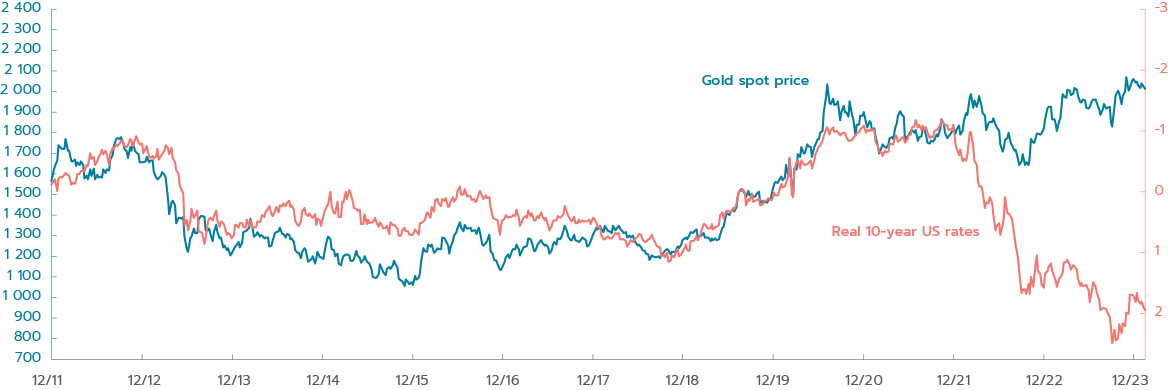

There is therefore a close connection between investors’ interest in gold and interest rates. However, inflation also enters into this connection, as it eats into investor remuneration. As a result, gold tends to be inversely proportional to real interest rates. For example, PIMCO, an investment firm, explained in 2014 that it considered gold to be a long-duration asset of duration 27 (i.e., a 1% shift of real rates in one direction triggers a 27% shift in gold in the other direction). Since then, with the emergence of ETFs, which have made the market more liquid, PIMCO estimates that gold’s duration has fallen go 22,2 (read here).

This is a long-term historical relationship but one that has recently loosened. For, gold has held up very well since the start of the latest central bank monetary tightening, in 2022, despite higher nominal rates and lower inflation – and, hence, despite the rise in real rates.

Past performances are not a reliable indicator of future performances.

There are three main explanations for this. First, gold is regarded by many financial investors as a “safe haven”, i.e., able to retain value during periods of uncertainty. This is due mostly to the fact that gold is a real asset, thus ensuring that it will never go bankrupt and that it will always offer investors residual value allowing them to wait for a return to better days.

In light of recent events – the war between Russia and Ukraine, severe instability in the Middle East after Hamas attack against Israel, and growing tensions between the US and China as globalisation appears to be running out of steam – some investors have chosen to retain an allocation in gold, despite its opportunity cost.

The other reason is the acquisition during this period of a large quantity of gold by central banks. Historically, central banks in developed countries were required to have gold in their safes to guarantee the redemption of outstanding banknotes, which were mere promissory notes held by citizens and payable by their government. And then, unofficially in 1971 and officially in 1976 with the signing of the Jamaica Accords, the convertibility of banknotes into gold, in place since the Bretton Woods agreements, was lifted. Central banks nonetheless kept gold on hand to “ensure” their solvency.

Over time and in reaction to various challenges, central banks sold off some of this gold at a pace of 400 to 500 tonnes per year in the 1970s and thereafter. European central banks (including Switzerland’s) went so far in 1999 as to sign the Washington Agreement capping their annual gold sales to keep from pushing down its price. The cap fluctuated between 400 and 500 tonnes of gold per year between 1999 and 2019, the year when the mechanism was ultimately set aside.

But things changed in the early 2000s. With the development of emerging market countries, countries whose central banks’ reserves rose were not those that were holding heavy inventories of precious metals. These central bankers then invested their reserves based on the same process as Western countries and began to massively acquire treasury bonds of major Western countries, along with… gold. This additional demand triggered an increase in gold prices, which, in turn, made Western banks less inclined to sell off their “barbarous relic”.

Meanwhile, the emergence of a very large middle class in emerging market countries (in China, for example, almost 350 million people were lifted up into the middle class within a few years) strengthened retail demand for gold in these countries, where it is regarded as a store of value.

The resulting skyrocketing in gold prices in the 2000s (the price per ounce rose from $280 in 2000 to $1900 in 2011) generated serious criticisms of governments that were sellers (with Gordon Brown’s government in the US and Nicolas Sarkozy, then finance minister in the government of Jean-Pierre Raffarin), which were accused of “selling off the family jewels”.

All in all, central banks in Western countries have phased out their sales, while central banks in emerging market countries have ramped up their buying. And, in 2010, central banks as a group moved from net sellers to net buyers. That trend has continued since then and, in 2019, we switched from a situation in which central banks were selling between 500 and 600 tonnes per year to one in which they were buying more than 600 tonnes per year.

This change was fundamental for gold, as central banks thus boosted demand by almost 1200 tonnes per year, or almost 25% of the annual market. This made central banks major players on the market, and their attitude to gold must be understood in assessing gold’s mediumterm potential.

While Covid caused central bankers to suspend their gold buying programmes in 2020 to devote their resources and energy to stabilising the financial markets, they have since resumed buying with a vengeance. In 2022, central banks acquired 1137 tonnes of gold, the most in volume terms since 1967.

And the trend spilled over into 2023, with buying reaching 1037 tonnes. The biggest buyers are still emerging market countries, led by China, as well as European countries like Poland and Hungary, which have also raised their purchases.

The main consumer sector is jewellery, which has been relatively stable over the years. Industrial demand accounts for only a small part of consumption for the moment and therefore varies little in the event of a strong economic acceleration or deceleration.

It is mainly financial demand that will constitute (or not) marginal demand for gold and help set its price. On this point, the role of central banks has been, and will remain, essential. They now seem to be long-term buyers of gold.

Investment demand from private actors varies with interest rate trends. This source of demand has shrunk over about the past two years, but it could be boosted by the looming end of the monetary tightening cycle and support gold prices.

It remains to be seen what attitude central banks will take in coming years. On this point, some possible answers come from the annual survey of central banks worldwide conducted by the World Gold Council. Released in late May 2023, the survey was conducted with almost 57 central banks, of which 13 in developed economies and 44 in emerging market and developing countries.

A total of 24% of central banks said they wanted to raise their gold allocation in the next 12 months, compared to just 3% that said they wanted to reduce theirs. The latter group included Turkey, which must manage a challenging financial situation, and Kazakhstan, which wanted to rebalance its portfolio after the steep rise in gold in recent years.

Even better, the survey asked central banks why they were buying. Their two main arguments of surveyed persons were gold’s lack of counterparty risk and real interest rates that are likely to “remain sustainably low”. Both of these arguments are essential. The lack of counterparty risk, first of all. For one of gold’s major qualities is its status as a real asset, which means it will never vanish, unlike a debt or a company, which respectively, may fail to be repaid or go bankrupt. This is why gold is regarded as a store of value, as anyone holding it will always have the opportunity of being made whole. This is an interesting point raised by central bankers when considering other assets in their portfolios, i.e., mainly government bonds, most of whose issuers are very heavily indebted (France and the US, for example, have debt/GDP ratios that are now higher than 120%).

Another reason cited for buying was stubbornly low real rates. This takes us back to the aforementioned link between gold and real interest rates. But it is especially noteworthy that central banks, which set interest rates in their respective countries, are saying that those interest rates cannot move back up.

This observation is no doubt due most of all to the fact that governments of the main developed economies are now very heavily indebted and that any increase in real rates would make debt servicing untenable. Hence, according to the US Congressional Budget Office, with the rise in interest rates over the past two years, debt-servicing costs could in coming years constitute the US’s top budget line item.

Moreover, as highlighted by Mario Draghi, a former president of the European Central Bank, in a recent speech, the world we live in has changed. We have gone from an economy in which central banks were meant to manage mainly demand-side shocks (i.e., declining consumption or, conversely, overheated consumption) to a situation of supply-side shocks. These are due in part to countries’ now looking inward after a long period of globalisation, as well as to the transformations of our economic systems, which are profoundly changing the nature of our needs. This is the case of the energy transition in particular.

The problem is that monetary policies (i.e., the use of interest rates to steer the economy) have little impact on this type of shocks. Moreover, it is hard and time-consumer to resorb supply-side shocks, something that can therefore trigger inflation that is more structural in nature. And, third, the need to transform our economies requires huge investments, which, in turn, require low financing costs.

Rates that are necessarily low, inflation that is more structural in nature – we understand better central banks’ attitude. This is no doubt also the third reason why gold has fared so well in 2023 and why it has become decorrelated from real rates. Some actors do not believe in a sustained rise in real interest rates, similar to what we have seen in recent months, due more persistent underlying inflation and a need for financing that could not bear too high rates for too long.

The energy transition that the world began after the 2015 Paris Agreement consists in replacing fossil fuels by technologies that will lower environmentally harmful CO2 emissions to zero by 2050. To do so, the world is counting mainly on developing renewable energies, led by wind and solar, and on electrifying our uses, particularly in the area of transport.

This shift will require a large quantity of metals to build all the energy producing vectors, wind turbines, solar panels and electric cars. CNRS, a French think tank, estimates that, over the next 30 years, the world will have to extract as much metal as since the start of human history.

But the energy transition has little impact on gold. As it is very expensive, gold is generally used in very few industrial applications. It is not currently used in low-carbon technologies. But things could change. The World Gold Council reports that photovoltaic panels using gold to enhance performances are now on the drawing table. Other projects are trying to use gold in passive airconditioning, such as gold flakes that, when enclosed in window panes, could be directed by electric current to block, or let in, solar rays.

But these technologies are still in the development stage and are unlikely to have any major impact on the gold market for several more years.

Completed on 05/03/2024

This promotional document was produced by Ofi Invest Asset Management, a portfolio management company (APE code: 6630Z) governed by French law and certified by the French Financial Markets Authority (AMF) under number GP 92-12 – FR 51384940342, a société anonyme à conseil d’administration [joint-stock company with a board of directors] with authorised capital of 71,957,490 euros, whose registered office is located at 22, rue Vernier 75017 Paris, France, and which has been entered into the Paris Registry of Trade and Companies under number RCS 384 940 342. This promotional document contains informational items and figures that Ofi Invest Asset Management regards as well-founded or accurate on the day on which they were researched. No guarantee is offered regarding the accuracy of information or figures from public sources. The value of an investment on the markets may fluctuate either upward or downward and may vary because of shifts in exchange rates. Depending on the economic situation and market risks, no guarantee can be provided that the products or services presented herein will achieve their investment objectives. Past performances are not a reliable indicator of future performances. The analyses presented herein are based on the assumptions and expectations of Ofi Invest Asset Management at the time this document was written. It is possible that some or all of these assumptions and expectations may not be borne out in market performances. They do not constitute a commitment to performance and are subject to change. This promotional document offers no assurance as to the suitability of products or services presented and managed by Ofi Invest Asset Management regarding the financial situation, the investor’s risk profile, experience or objectives and constitutes neither a recommendation, nor advice, nor an offer to buy the financial products mentioned. Ofi Invest Asset Management declines any liability for any damages or losses resulting from the use of all or part of the information contained herein. Before investing in a fund, all investors are strongly urged to review their personal situation and the benefits and risks of investing in order to determine the amount that is reasonable to invest, but without basing themselves exclusively on the information provided in this promotional document. Cover photo: Shutterstock.com. FA24/0082/05032025.